Just because it’s covered doesn’t mean it’s covered

In this post, Jeanna Holtz, director of health financing on SHOPS Plus project, takes a deeper look at effective coverage of family planning under health financing initiatives for UHC.

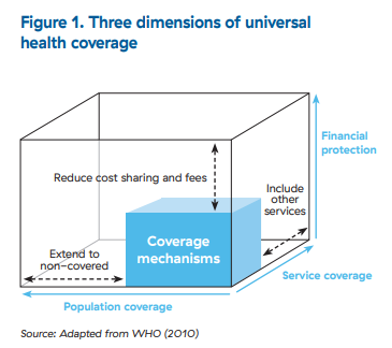

There’s no way around it: advancing toward universal health coverage (UHC) and providing universal access to family planning (FP) is a complicated, lengthy process. It requires tackling persistent and diverse barriers that are financial, political, social, and behavioral in nature. Under UHC, “coverage” encompasses three main dimensions, represented by the WHO’s “UHC cube”: who is covered; what services are covered; and what proportion of cost is covered (financial protection) (Figure 1).

In this context, the FP community has a keen interest in making the full range of contraceptive services accessible within broader initiatives to expand health coverage, particularly to underserved populations such as youth or the poor. To do this, immediate priorities are to include the full range of FP services in benefit packages covered by health insurance and other health financing programs, and to secure resources to pay for them. There remains much to do at this level, as many programs cover and fund FP just partially, or not at all. Three reasons for this are:

- Competition for scarce resources. FP competes for limited public resources within the health sector and across other sectors such as education or energy. Governments tend to prioritize urgent health needs (e.g., COVID-19, life-saving treatments) at the expense of covering and funding FP. For instance, the Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition estimates that in USAID’s 26 priority countries, even if donor support remains constant, there will be a funding gap of USD 146 million for contraception supplies by 2025, due to projected growth in the number of FP users.

- Political and social realities. Pressure to limit or exclude FP from benefit packages creates gaps in coverage. For example, LARCs might be covered while short acting methods are excluded, based on the historic availability of short acting methods free of charge to clients from public or other subsidized locations. In another scenario, permanent methods may be covered for post-partum clients only, or clients over a certain age, reflecting social or religious norms.

- Focus on catastrophic health events. Historically health insurance programs were designed to pool risks of health events that are expensive, low-frequency and randomly occurring (e.g., a bone fracture). Insurance programs pay for covered health events using funds contributed in advance by beneficiaries. They often exclude or limit “routine” lower-cost but high-frequency, cost-effective health services such as FP (particularly short-acting methods). This mismatch between supply and demand is one of a host of reasons people may not value insurance, and insurance programs may struggle to scale up and be financially viable.

_Jeanna Holtz.jpg)

Covering FP in a benefit package does not guarantee that it will actually be covered in practice, however. To understand more, it’s helpful to consider elements of effective coverage (Ng 2014).* Effective coverage is a more holistic view of UHC that considers population need, use, and quality. This richer examination of coverage helps isolate factors that enable or inhibit access to FP. Factors that influence effective coverage of FP include how providers are paid; which providers are contracted with health financing schemes; out-of-pocket costs borne by clients; the quality of care delivered; the country’s political, social, and economic context; and treatment-seeking behavior and preferences of citizens.

To illustrate, consider how a provider payment mechanism and rates can influence effective coverage of FP. Provider payment mechanisms range from input-based financing such as a budget or grant, to output-based options ranging from fee-for-service, case rates or per-capita (capitation) payments. The nature of the payment mechanism, and the amount it pays by FP method create varying financial incentives and disincentives for providers. For example, a fee-for-service payment can incentivize a provider to deliver a higher-paying LARC method, assuming the payment is adequate and sufficiently higher than for short-acting methods.

In contrast, capitation payments reflect a fixed prospective amount paid per client, per period, regardless of the services used by the client. In this case providers can have a financial incentive to discourage clients from choosing a LARC method that is more expensive to deliver or any method at all, or simply refer the client to obtain her method of choice from another provider. This bias can limit choice for clients, disrupt their care and cause them to incur more out-of-pocket costs.

Many countries are making progress to advance toward UHC and meet goals for FP, but there’s important work to be done. Advocates for FP can champion the opportunity to more effectively cover FP. They should build the case on what works and what does not to inform better programming, for example, on how different payment mechanisms affect provider behavior. They can promote public-private engagement through contracting to tap the resources of the entire health system, including those of the many small and medium private providers of FP who deliver services in underserved communities. This is a long-term endeavor. Gains will be met with setbacks, but we’re moving in the right direction.