Lessons Learned

Photo: KC Nwakalor

Any framework that seeks to improve quality of care will need to address issues at several levels of the health system. Common critiques of quality assurance and improvement interventions are that they are either too narrow in focus to account for other factors that determine success, or so broad and complex that they make it impossible to determine which input(s) were successful. A comprehensive process is needed. However, many health systems struggle to provide successful and sustained quality assurance and improvement interventions because factors such as enhancing provider knowledge, measuring treatment outcomes, or patient satisfaction are measured in isolation. To date there has not been enough focus on providing effective people-centered care that takes numerous quality factors into account. By necessarily addressing complex and numerous inputs that contribute to quality of care, health systems can begin to emphasize the core goal of preventing illness and promoting well-being. To support this, a recent report published by WHO, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the World Bank Group, Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative for Universal Health Coverage, highlights the need for building quality into the foundations of health systems by focusing on the following priorities:

- Establish an effective health care workforce

- Achieve excellence across all health care facilities

- Deliver safe and effective medicines, devices, and other technologies

- Ensure effective use of health information systems

- Develop financing mechanisms that support continuous quality improvement

Focusing on these priorities can help guide actions to improve the quality of care among private health entities and the broader health system. This brief uses these actions as a framework to present country examples of SHOPS Plus efforts to address the quality of care among private providers and identify lessons learned.

Establish an effective health care workforce

Providers should be equipped with the knowledge, skills, and abilities to deliver quality health services. Numerous targeted interventions can be used, ranging from timely updates and dissemination of evidence-based protocols and guidelines to more direct approaches such as clinical training, continuing medical education courses, supportive supervision, and coaching and mentoring to improve provider knowledge and skills.

Clinical trainings are perhaps the most common technical intervention that governments and implementing partners use to improve the quality of the health care workforce. Bluestone and her colleagues8 found that the most effective educational techniques are case-based learning, clinical simulations, and practice with feedback. Didactic techniques such as lectures were found to have little or no impact on learning outcomes. An example of hands-on learning is a low-dose, high-frequency training approach pioneered by the United States Agency for International Development’s Maternal and Child Survival Program. This is “a capacity-building approach that promotes maximal retention of clinical knowledge, skills, and attitudes through short, targeted in-service simulation-based learning activities, which are spaced over time and reinforced with structured, ongoing practice sessions on the jobsite.” This approach can be used for both pre-service and in-service training. In Liberia, faculty and preceptors who are responsible for teaching midwifery students often lacked the clinical skills to effectively teach students. To address this, the Maternal and Child Survival Program improved the capacity of faculty and preceptors and the quality of pre-service education using a low-dose, high-frequency training approach. Post-training test scores show that participants’ skills continued to improve through the approach. The average post-test score was 90 percent for the immediate post-training test9 (MCSP 2019). In a pre-service context, access to real-world clinical environments is often a challenge for the private sector. The following case study from Tanzania illustrates how SHOPS Plus sought to address such a challenge.

Case Study |

Developing a national strategy to address gaps in pre-service education in Tanzania |

| Lessons learned |

|---|

| Designing a model for promoting quality with only the public sector in mind can result in exacerbating quality challenges in the private sector. Programs and planning should consider the whole health system in addressing health workforce challenges. |

| Encouraging participation of private sector stakeholders whose voices have not been sufficiently heard is essential to articulating the issues and identifying the root causes of health workforce problems. Only then can solutions be developed to meet their needs. |

| Facilitating—rather than leading—public-private stakeholders to engage in joint discussions through co-creation roundtables and other participatory approaches can deepen stakeholders’ ownership of activities and encourage sustainability of a high-quality health workforce. |

Achieve excellence across all health care facilities

Enhancing provider knowledge without addressing the environment in which they are expected to practice is a common oversight in private sector-focused quality of care efforts. Ensuring service readiness in the clinical practice environment and conducting regular facility assessments are important to ensure health providers and their leaders are positioned to provide excellent quality of care across facilities. The clinical practice environment is the physical environment in which providers are expected to implement their skills and deliver their services. Improving providers’ knowledge and skills does little to strengthen quality if they lack the necessary supplies, equipment, and infrastructure to provide services. Since many non-networked providers operate largely independently, they need support determining the gaps in their practice environment and knowing how to address them.

Assessments of facilities combined with mentorship can strengthen the practice environment and improve quality of care outcomes. For example, the Mentorship and Enhanced Supervision for Health Care and Quality Improvement program by Partners in Health used mentorship as a key intervention to improve quality among public sector nurses in Rwanda. Mentors used structured checklists to gather quality of care information during their visits to health centers and provided one-on-one mentorship and learning sessions at the facilities. The mentors and health facility team worked together to identify gaps in administration, procedures, and the supply chain that could be addressed through targeted, collaborative interventions. Nurses improved their quality of care as a result of the program, with correct diagnosis increasing from 68 percent in 2014 to 94 percent in 2015. While the program was successful, there were challenges including logistical issues such as transportation for the mentors to remote areas. Additionally, the program found that staff turnover could reverse any gains made in a facility. Nevertheless, the program shows that improving the practice environment is a promising way to improve quality across many health areas. A key lesson learned was to work with the existing public health system, rather than creating parallel systems, to increase sustainability.10

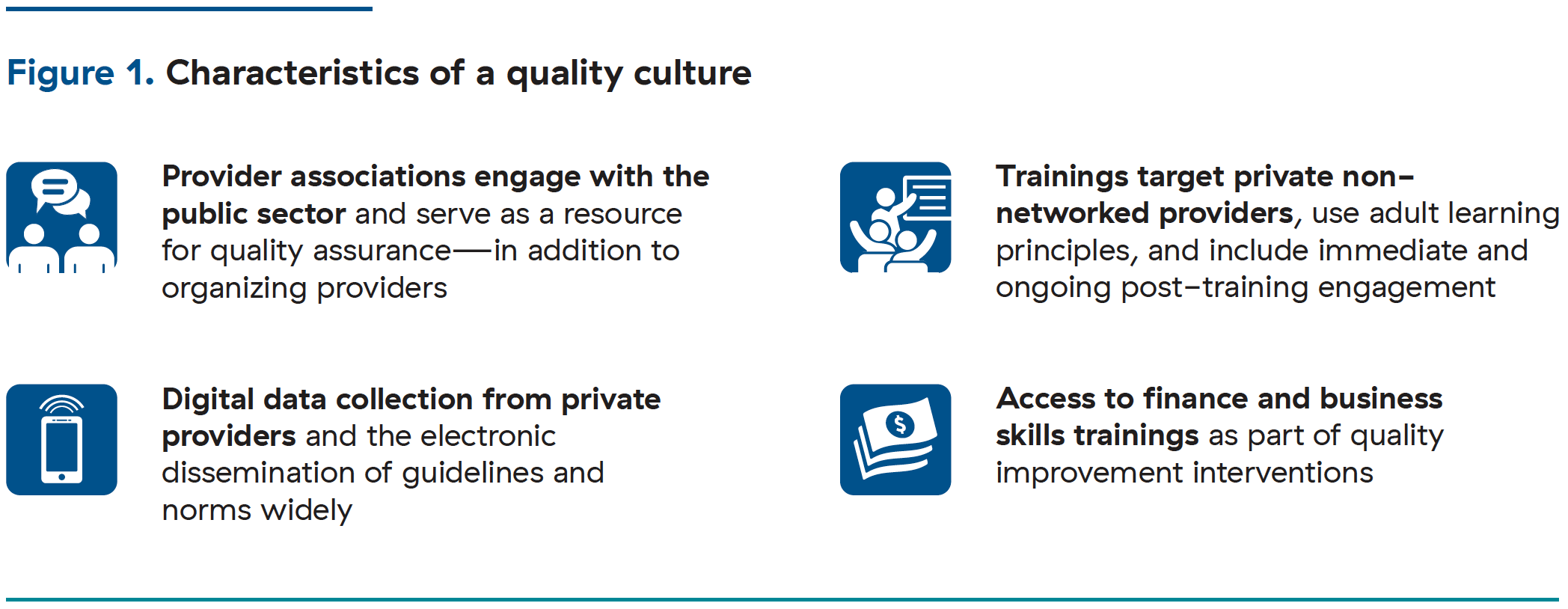

Interventions that focus on identifying facility-level gaps and mentorship in the practice environment are equally critical to institutionalizing a quality culture (Figure 1) in routine private practice. This approach can be seen in SHOPS Plus’s adaptation of a public sector methodology for the private sector in Senegal.

Case Study |

Strengthening the family planning practice environment for Senegalese private providers |

| Lessons learned |

|---|

| Knowledge gaps can be addressed through coaching, but structural gaps in the facility and practice environment (such as a lack of equipment or commodities) require either a strong partnership with government or increased access to finance for providers. |

| Government partners, including those at the subnational level, should be consulted early on to strengthen commitment to provide needed resources to address practice environment gaps. |

| Governments may be open to providing commodities, equipment, and other resources needed to strengthen the practice environment in exchange for regular reporting of data. Support to private providers should include training on reporting through established information management systems such as DHIS2. |

Deliver safe and effective use of medicines, devices, and other technologies

Access to reliable and quality medicines, devices, and other technologies is a basic requirement in ensuring a high standard of health service delivery. Regulation can ensure quality products on the market and proper provider training can ensure their appropriate use. Injectables are the most commonly used method in many sub-Saharan African countries. DMPA-SC uses a small needle that allows for subcutaneous injection. It is considered by many to be a safe and effective, low-dose product that comes with fewer side effects than other injectable options. The product allows for the possibility of self-injection, which empowers women in their fertility decision making. Introduction of this revolutionary product by PATH into four countries required tracking product registration, guiding the product introduction plans through the review and approval processes, and guiding quantification exercises. It also required adapting provider training materials developed by PATH, so that providers could gain the skills to safely administer the product and counsel patients on the method. Nearly half a million doses of DMPA-SC were administered over two years in Burkina Faso, Niger, Senegal, and Uganda—29 percent of which were to first-time family planning users. 11

The introduction of DMPA-SC shows that to ensure safe and effective use of new medicines, stakeholders need to take a comprehensive approach that also seeks to strengthen the enabling environment, prepare for product distribution, and train providers. This can also be seen with the introduction of chlorhexidine in Ghana by the SHOPS project.

Case Study |

Improving the quality of neonatal care by introducing chlorhexidine in Ghana |

| Lessons learned |

|---|

| Getting new products or technologies onto essential medicines lists and on medicine lists for national health insurance schemes can position the government as a champion of ensuring the availability of quality products. |

| Three service delivery levels should be considered when introducing a new product: the retailer (pharmacies and over-the-counter medicine sellers), the provider (midwives), and the end user (caregivers). Interventions need to be targeted at these levels to ensure a high quality of service delivery. |

Ensure effective use of health information systems

Effective health information systems improve clinical governance. They enable stakeholders to make better resourcing decisions and providers to make better care-related decisions. Jhpiego’s Expanding Maternal and Neonatal Survival project leveraged data visualization to improve the quality of care in hospitals in Indonesia. The project invested in systems to collect information at all levels and to strengthen data quality. It made the data available to staff at health facilities using wall charts. These data helped hospital administration make timely management decisions. It also helped midwives and facility teams improve the quality of their work by enabling them to refer to the performance data on a regular basis. Expanding Maternal and Neonatal Survival demonstrated the importance of delivering quality services. In Nigeria, SHOPS Plus developed an app aimed at collecting tuberculosis (TB) data more efficiently.

Case Study |

Developing an app to improve efficiencies in TB data collection in Nigeria |

| Lessons learned |

|---|

| Digital tools have the potential to improve the delivery of services, but they need to be flexible and designed with the end user in mind. Hosting multiple user-centered design workshops and testing and re-testing a theory of change and design can ensure that the tool best fits the needs of the private sector, including non-networked providers. |

| The motivations of an end user and possible incentives to ensure the use of an app must be considered. This is especially important for private health providers who often need to be encouraged to report data. |

Develop financing mechanisms that support continuous quality improvement

Unlike public sector facilities, the ability of a private facility to financially invest in quality improvement at its discretion can have both positive and negative effects on service delivery. In the public sector, government budgets fund quality assurance and improvement investments. Private sector facilities must find or raise discretionary capital to invest in their practice environment and quality of care initiatives as part of routine business practice. Facility managers, who are often clinicians, may have limited business acumen and require support to improve their managerial capacity and access financing. If improvements were made in these areas, managers could more easily pay and retain staff, as well as purchase the supplies and equipment needed to deliver quality services.

Photo: Jeanna Holtz

Gaining business skills is one of many benefits afforded to members of social franchises. In 2012, with support from Africa Health Markets for Equity, PS Kenya introduced the Tunza Business Skills program to improve providers’ entrepreneurial skills. In addition to business support, the program helped fund quality improvement initiatives and facility expansion by linking franchisees to affordable financing. The program has strengthened quality of care; 30 facilities improved by one full level in SafeCare accreditation from 2017 to 2018. Many of the Tunza facilities also saw business growth. Collectively, the facilities demonstrated a 15 percent improvement on measured scores of management and leadership, human resource management, facility management, and support services. As the program evolved, it adapted its approach. Similar to clinical skills, the project learned early that training alone would not be sufficient to improve managerial or business performance. As each facility has its own unique gaps, strengths, and needs, each is best served with tailored, in-person managerial support and on-the-job coaching. Therefore, each facility in the program was equipped with a business improvement plan tailored to its specific needs and a business advisor to assist the facility in implementing it.12

Private providers and facilities that are part of a network often have access to this type of tailored support. However, non-networked private providers do not often possess the same opportunities. The SHOPS Plus program in Madagascar offers an approach to building managerial capacity among providers who do not participate in a network.

Case Study |

Building the business skills of private providers in Madagascar |

| Lessons learned |

|---|

| While business skills and access to finance may not always be associated with clinical quality, they equip providers with the resources to sustain their facilities as businesses and ultimately deliver quality services. |

| Improving business management skills yields two benefits. First, providers build their confidence and make more informed investment decisions and access finance wisely. Second, they become more viable lending targets for financial institutions, which allows them to more sustainably and efficiently address capacity gaps. |